Cultural Influence in Caregiving

I recently had the pleasure of speaking at the Aging Conference hosted by Living Systems Counselling. My presentation was on Navigating Caregiving from a Cultural Perspective—drawing from my husband’s personal story of caring for his father with dementia, and using Bowen Family Systems Theory to think through caregiving in a cultural context.

Cultural influence is something I’ve always had a deep interest in. In Chinese culture, filial piety has been a foundational value for thousands of years. Yet, a question that often stays with me is:

“Does honouring one’s parents mean we need to lose ourselves?”

This question becomes especially relevant when caregiving often makes the line even more blurry during the process.

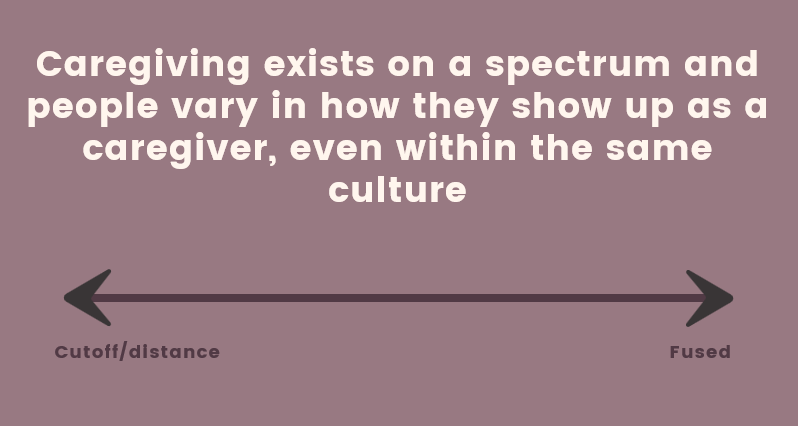

Caregiving Exists on a Spectrum

My training in Bowen Family Systems Theory has given me a framework to think about this more clearly. Bowen proposed that there are two life forces in every relationship system:

- The togetherness force, which “assumes responsibility for the happiness, comfort, and well-being of others.”

- The individuality force, which “assumes responsibility for one’s own happiness, comfort, and well-being.”

When these two forces are out of balance, we may become too fused (overinvolved) or too distant (underinvolved) from our family. I believe caregiving exists on a spectrum. Even within the same culture, people vary greatly in how they show up as caregivers.

Across all cultures, there are three caregiving patterns which I called fused caregiving, distant caregiving and differentiated caregiving.

1) Fused Caregiving (Overinvolved)

A fused caregiver tends to take on too much responsibility, often neglecting their own needs in order to meet family expectations or avoid guilt. It becomes hard to tell where their thinking ends and the family’s expectations begin.

Examples may include:

- Checking every little detail at a parent’s care home

- Feeling like they have no choice but to take on everything

- Cancelling social plans and hobbies to stay available 24/7

- Feeling guilty for taking breaks or asking for help

2) Distant Caregiving (Underinvolved)

A distant caregiver tends to emotionally or physically distance themselves from their parents to avoid being overwhelmed. Tasks may still get done, but with little emotional engagement.

Examples may include:

- Leaving most care to professionals and checking in only occasionally

- Providing financial support but avoiding visits or having deeper conversations

- Thinking, “The staff are professionals—they’ll take care of them better than I could anyway.”

3) Differentiated Caregiving (Balanced)

Differentiated caregiving is when someone stays emotionally connected to their family while also acting according to their own values and principles. Decisions are made thoughtfully, balancing both the parent’s needs and their own well-being.

Examples may include:

- Recognizing limits and setting boundaries around rest or personal time

- Initiating difficult conversations in a calm manner: “I want to honour Dad by making sure he’s well cared for, but I can’t do everything myself. Can we talk about what each of us can realistically do?”

- Being willing to ask friends and family members for help

- Staying emotionally present with the parent, showing care and patience

Moving Toward Differentiated Caregiving

In collectivist cultures, the pressure to “do more,” “stay quiet,” or “keep the harmony” can be stronger. Yet even within these cultures, all three caregiving patterns still exist—fused, distant, and differentiated—just in varying degrees.

Being a differentiated caregiver doesn’t mean others will never get upset with them, in fact, quite the opposite. When others’ expectations aren’t met, it’s almost predictable that they may feel disappointed or want the caregiver to change. Learning to sit with that discomfort is part of the differentiation process. Differentiation isn’t about never upsetting others; it’s about showing up authentically, in a way that respects both yourself and your family.

Differentiation also doesn’t mean a caregiver is free from realistic constraints. There are often difficult stressors, such as limited financial resources or being the only child. Rather, differentiation is about how caregivers relate to these constraints. Even when choices are limited, caregivers can still differ in how thoughtfully they make decisions. You may find families facing the exact same limitations and circumstances, yet how they approach the situation can look very different.

Moving toward differentiation takes courage, and it’s rarely a linear path. When family tension and anxiety run high, it’s easy to slip back into old patterns. Awareness is the first step toward slowing down the process so that caregivers don’t automatically react to situations.

Here are some reflection questions to help you get started:

- What situations tend to trigger feelings of guilt, fear, or resentment in me?

- How do I usually respond when caregiving becomes stressful?

- What does filial piety personally mean to me?

- What does honouring my parents look like in my own life?

- How do I want to show up as a son or daughter, regardless of what others expect of me?

- What are my own limitations or non-negotiables?

- How can I stay connected with my parents while respecting my own limits?

If this topic resonates with you, you can read more insights from the Living Systems Conference Takeaways here or purchase the recording here.

Thanks for reading!

Until next time,

Maybo